In the Church but not of the Church

When Adam was told to sacrifice the first born of his flock, when Abraham was told to sacrifice his only son and when Joseph Smith was told to sacrifice his monogamous relationship with his wife, they were not given any kind of reason or justification. Rather, their response was along the lines of “I know not [why], save that the Lord hath commanded.” They were expected to comply even though they did not know and thus could give no reason to anybody who might ask, “Why?” – and we have every reason to believe that other people definitely did so ask.

Imagine, now, that as Eve, Issac and Emma eventually come around to complying with these instructions as well, others ask them, “Why?” Again, their corresponding prophet figures never did – or never could give them a reason that would satisfy such questions. Furthermore, these people (some more than others) did not waver in the face of such relentless criticism – for that is exactly what unanswered questions which are incessantly asked amount to.

Like Eve, Isaac and Emma, we too have been told in so many ways that we are to receive the will of the Lord through our priesthood leaders. “Whether by mine own voice or by the voice of my servants, it is the same.” (D&C 1) “No one shall be appointed to receive commandments and revelations in this church excepting my servant Joseph Smith… And thou shalt be obedient unto the things which I shall give unto him, even as Aaron… And thou shalt not command him who is at thy head, and at the head of the church.” (D&C 28) “He that is ordained of me shall come in at the gate and be ordained as I have told you before, to teach those revelations which you have received and shall receive through him whom I have appointed.” (D&C 43) In our meetings we are asked to raise a sustaining hand. In our worthiness interviews we are asked if we sustain them as prophet, seers and revelators.

All of these passages and policies serve put us in the same relationship to the church leaders as Eve, Isaac and Emma were to Adam, Abraham and Joseph. Just like them, we will be given instructions which we do not like or understand. Similar to their cases, our church leaders often will not and sometimes cannot give us the reasons or explanations when we ask, “Why?” Furthermore, just like these people, we will also be unable to provide reasons when those around us ask, “Why?” This is what being a faithful member of the church entails.

It is also the reason why the church and its faithful members will always be persecuted by the world around them – especially within a democratic society. A democratic society is grounded in people’s ability to request, give and respond to reasons and explanations so as to check and balance all authority figures. The world thus teaches that authority figures ought only to be accepted as such to the degree that they are able to provide good answers to the question: “Why?” Unsurprisingly, the good people within our society regularly ask us members of the church to give reasons for our policies and doctrines. As I have argued, however, part of being a faithful member of the church entails that we will often not be able to give such reasons and as such will refuse to subject our authority figures to the checks and balances of democratic society. This, then, leaves the democratic world around us with nothing but irrational and sometimes violent means by which to check and balance the authority figures and the influence they have in our shared world. In other words, our unwillingness/inability to provide reasons for our doctrines and policies flies directly in the face of the democratic world around us – a fact which naturally entails their inevitable persecution of us.

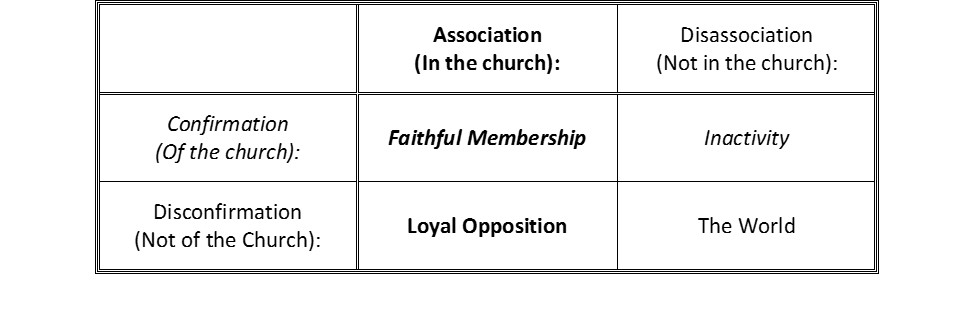

We are thus each and every one of us in the church presented with two decisions which we must prayerfully make for ourselves. Will we be in the church? Will we be of the church? I would like to briefly unpack these questions, questions which will then allow us to organize our relationship to the church and its leaders along two relatively independent axes that correspond to these two questions.

In order to understand the independent axes along which we can describe our relationship to the church, it will be necessary to disentangle two separate actions which are often conflated within the church (especially within the bloggernacle): disassociation and disconfirmation. The former involves simply disengaging from the church and going one’s own way. The latter involves actively checking, correcting or undermining the church and its leaders. I cannot stress the importance of this distinction enough.

Voluntary disassociation from the church and its leaders is the primary mechanism within the church for checking and balancing church leaders and their authority. We are constantly encouraged to confirm our testimonies, not just of gospel doctrines taught within the church, but of the men who represent and direct it. This is no formality, for it is the relative ease within which we are able to distance ourselves from the church that sets it in stark contrast to worldly political tyrannies. To repeat, the church not only tolerates but actively encourages us to pray about our relationship to the church and its leaders. The church also encourages us voluntarily disassociate ourselves from it and its leaders if the spirit so moves us. The church will never force us to accept and sustain its leaders as prophets, seers and revelators.

Vocal disconfirmation of the church and its leaders, by contrast, is the primary mechanism within a democracy for checking and balancing all authority figures. It is to incessantly ask “why?” questions which have not been answered. It is to actively call for a change in policy or doctrine. As noted, such attempts at checking and balancing the authority of the church and its leaders will always come from outside the church. We would expect nothing less from a well-functioning democracy. Such attempts at checking and balancing the authority of the church and its leaders does not, however, have any legitimate place within the church. Being “of” the church means to understand and acknowledge that occasionally our leaders will be unwilling or unable to respond to questions of “why?” and to accept and follow their instructions all the same.

We can thus divide the relationships which people might have to the church and its leaders into four basic categories: those who are neither in the church nor of the church, those who are not in the church but are of the church, those who are in the church but not of the church and those who are both in the church and of the church.

I have already discussed those who are neither in the church nor of the church. These are the good citizens of the liberal democracies in which we live, or as we call them, “the world”. They are not members of the church in any way and view its authority and that of its leaders like they do any other authority figure – with suspicion and doubt. They will never cease asking the church why it believes and behaves as it does. When the church is unable to give adequate reasons for these things – and it will never be able to give fully adequate reasons – the world will persecute the church in an effort to change, if not destroy it. It will protest. It will continue to ask embarrassing questions. If needs be, the world will occasionally get violent with the church if that is what it takes to disconfirm it.

The second group includes those who have a strong testimony of the church and its leaders, but feel compelled to disassociate with them for some reason or another. These are members with varying degrees of (in)activity. Such people do support the church leaders’ exclusive right to receive instructions for the church and to pass them on to the general membership. Many of these people have, however, been prompted by personal revelation to not follow some of the church leaders’ instructions. These people, I strongly suspect, are far more numerous than we might expect for the simple reason that these people do not publicly speak about or advocate their disassociation from the church. They disassociate from, but do not disconfirm the church and its leaders. While the church wishes such people would fully integrate themselves within the faithful fold, it wants even more for them to follow the Lord in their personal lives.

The third group consists of those who are in the church but are not of the church. These are people who have not disassociated from the church despite their rejection of the leaders’ prerogative to represent and direct the church without a sufficient explanation or reason. These are people who identify more with the democratic way of checking church authority than with the church’s way of doing so. Consequently, they will resist disassociating with the church precisely in order to disconfirm some doctrine or teaching within it, for this is the way that authority must be checked and balanced within the democratic world. Whether these people are sincere or not in their repeated questioning, “why?” does not matter. What matters is that these people, through their vocal questioning, petitioning and protesting chaff at and undermine the authority of the church leaders. These are the self-proclaimed “loyal opposition” whose behavior, the church leaders have insisted, has no legitimate place within the church.

Finally, we have the fourth group which consists of those who are both in the church and of the church. These are the people who keep their covenants to sustain the church leaders as prophets, seers and revelators who are under no obligation to give or respond to reasons for their instructions. These people know and accept the fact that the democratic world around them will never agree with them precisely because of their irresponsiveness of reason. The explanation for this is that they have received a personal revelation which – unlike the inactive member – has confirmed their support for the church and its leaders, even if they do not understand why.

To be sure, these four categories represent over-simplifications that will rarely, if ever, perfectly match up with any individual. It is better, I think, to construe these categories more as a bidirectional spectrum like unto the political compass. Horizontally, we can ask to what degree we have voluntarily aligned our own beliefs and behaviors in our own lives with the instructions of the church leaders? Vertically, we can ask how supportive or condemnatory we publicly are of the church leaders’ authority to instruct the general membership without answering to the checks and balances of the democratic world? While I acknowledge that we are in no position whatsoever to judge a person’s horizontal position on this scale, I submit that church members are well within their rights in criticizing and calling people to repentance based on their vertical position.

Whether by mine own voice or by the voice of my servants, it is the same.

Hmm, there’s much more to it than that. The verse reads:

So when servants accurately quote the word of the Lord it is the same, when they don’t it isn’t the same because then they are just sharing opinion.

Comment by Howard — July 3, 2014 @ 10:52 pm

For all things must be done in order, and by common consent in the church, by the prayer of faith.

Comment by Howard — July 3, 2014 @ 11:08 pm

I gave several references. You’ll have to do a lot more than drop a fairly ambiguous quote to address that part of the post.

Comment by Jeff G — July 3, 2014 @ 11:40 pm

Oh I know Jeff, your apologetics are always so air tight but I though it would be good to consider a little broader view. Lately it seems all of your creative paths lead to the same conclusion; obey priesthood authority! Just because! It’s almost like you start with that premise…oh wait, you do!

Comment by Howard — July 4, 2014 @ 6:07 am

I, for one, agree with Howard on the implications of D&C 1. But to the extent that D&C 26:2 comes up in these types of discussions, it seems mostly to be used as a justification for arguing that the Church is doing something wrong with nary a suggestion for how the Church could do it right.

Howard, do you advocate a literalist interpretation of 26:2 whereby a branch in Brazil cannot hold a bake sale without the vote of the entire Church at a general conference? Or do you read “common consent” as “the Church votes on major issues and the result of that vote is binding even on the GAs”, like the RLDS/CoC does? And, if the latter–what do you do about the fact that a (often sizeable) minority have not, in fact, consented to that course of action? Or is their staying in the Church in the wake of an adverse vote considered “consent” and, if so, how does that ultimate “the membership consents in that they can vote with their feet” position contrast with what the LDS Church does?

If you want to argue that the Church is applying D&C 26:2 incorrectly, show me what it would look like to apply it correctly. Otherwise, I’m likely to conclude that you view “common consent” not as an end to itself; but as a means to attain another goal (such as turning the Church into a puppet for largely secular, progressivist agendas)

Comment by JimD — July 4, 2014 @ 9:05 am

My 3 was more in reference to his 2 than to his 1. I think he may have a point about D&C 1, but he is going to have to say a lot more about the common consent passage for it to become directly relevant. After all, I see no reason why it cantbe construed along the lines of disassociation rather than dis-confirmation.

Howard,

I find it very ironic that you fault anyone for being a one trick pony. I can’t help but note a parallel similarity in all of your comments.

Comment by Jeff G — July 4, 2014 @ 9:27 am

I like what Elder James E. Faust said in Oct 1989 General Conference.

“I do not believe members of this church can be in full harmony with the Savior without sustaining his living prophet on the earth, the President of the Church. If we do not sustain the living prophet, whoever he may be, we die spiritually. Ironically, some have died spiritually by exclusively following prophets who have long been dead. Others equivocate in their support of living prophets, trying to lift themselves up by putting down the living prophets, however subtly.”

“This Church constantly needs the guidance of its head, the Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ. This was well taught by President George Q. Cannon: “We have the Bible, the Book of Mormon and the Book of Doctrine and Covenants; but all these books, without the living oracles and a constant stream of revelation from the Lord, would not lead any people into the Celestial Kingdom. … This may seem a strange declaration to make, but strange as it may sound, it is nevertheless true.”

Comment by Jared — July 4, 2014 @ 9:31 am

JimD,

No, I’m not a literalist but common consent has apparently been usurped by the (nearly compulsory) sustaining show of hands ritual which apparently is interpreted these days by apologists to be a blanket approval *in advance* of what ever the brethren do or decide. Is this common consent? Well starry eyed TBMs might argue yes because they have laid down their agency to church leadership. But is that what was intended by all things being done by common consent? No, if that were the case what is the point of mentioning common consent at all and what was the big deal about the war in heaven over agency if we are supposed to just hand it over to our Bishop? So the current practice isn’t by common consent at all. What would common consent look like? I’m not sure but it would be a lot more interactive than words flow downward and money flows upward.

Comment by Howard — July 4, 2014 @ 9:34 am

“So the current practice isn’t by common consent at all. What would common consent look like? I’m not sure but it would be a lot more interactive than words flow downward and money flows upward.”

You’re not sure what comment consent would really look like, but you constantly harp on how it’s currently practiced wrongly in the church. You’re a fascinating character, Howard-soul.

Comment by Michael Towns — July 4, 2014 @ 10:51 am

*common

Comment by Michael Towns — July 4, 2014 @ 11:01 am

I found the distinction between dissociation and dis-confirmation to be very helpful. I think you did a good job of charitably describing these categories.

Comment by Eric Nielson — July 4, 2014 @ 11:03 am

Well Michael I did out my reasoning, did you miss it? Now I invite you to describe how common consent is currently practiced and how that is correct.

Comment by Howard — July 4, 2014 @ 11:04 am

lay out

Comment by Howard — July 4, 2014 @ 11:05 am

Howard,

I have not merely assumed but have now produced numerous arguments in favor of authority. You might not agree with them, but they are there. You, by contrast simply assert without support or articulation that your view of revelation and the church is true. Who is really begging the question here?

Comment by Jeff G — July 4, 2014 @ 11:24 am

Lol!

Comment by Howard — July 4, 2014 @ 11:26 am

4 May 2007

Individual members are encouraged to independently strive to receive their own spiritual confirmation of the truthfulness of Church doctrine. Moreover, the Church exhorts all people to approach the gospel not only intellectually but with the intellect and the spirit, a process in which reason and faith work together.

Comment by Howard — July 4, 2014 @ 11:43 am

Howard, for what it’s worth, your paradigm of “words flow downward, money flows upward” is precisely the opposite of my own experience in the Church; on both counts. Also, the “war in heaven” analogy you draw seems problematic because that war culminated with the expulsion of the dissenters.

Otherwise my response is the same as Michael Towns’ – how can you say something is absent when you don’t even know what that something would look like if it were present?

Comment by JimD — July 4, 2014 @ 12:10 pm

So what is agency without choice JimD? Are you arguing common consent is alive and well in the church? If so, please point it out, describe it. If you are arguing more words flow upward than downward and more money flows downward than upward you are kidding yorself, it is overwhelmingly the opposite.

Comment by Howard — July 4, 2014 @ 12:25 pm

With all due respect, Howard, you were the one who broached the topic of common consent by hinting it was absent from the church. If you want me to think the church is violating a law, the first step is for you to define the elements of that law and explain how those elements relate to each other. Otherwise we’re just chasing our rhetorical tails.

Words don’t flow upwards? Howard, not all of us just sit in the pews every Sunday stewing about how much we loathe local leadership. Lots of us actually take our concerns directly to them and try to work something out. And plenty of money flows downwards–both in monetary and in-kind benefits to individual members in need, and in benefits to the congregation as a whole (meetinghouses, church camps, events, scout registrations, etc); as well as subsidies to particular programs like the CES and PEF. Yeah, some congregations pay in more than they get back–so that less affluent congregations can get more than they pay in. I thought you [i]liked[/i] redistribution?

Comment by JimD — July 4, 2014 @ 1:16 pm

Howard,

I still don’t see how that quote contradicts anything I’ve said. Maybe if you presented an detailed analysis between two perspectives I might be able to see what you’re saying a little better. From my perspective, common consent is alive and well both in the unanimity of the quorums and the public sustaining of leaders. If you are looking for a more democratic version than that I would recommend Protestantism.

By the by, why are you so hostile to authority? I’m hardly arguing (by abduction not deduction) that authority is the primary moral imperative, just a moral imperative and the entire bloggernacle screaming “authority worship!”

Comment by Jeff G — July 4, 2014 @ 1:35 pm

Jeff, I really have a great many problems with any paen to blind obedience. I immediately think of the Eichmann defense, “I was simply following orders.”

That was supposed to excuse his masterminding the German transportation system to send as many Jews to the extermination camps as possible. He, of course, bragged of sending 5,000,000 Jews to their death.

Let me put it simply. If you were at Mountain Meadows and local church leaders asked you to shoot men, women and children, would you have grabbed your weapon and helped exterminate them? If no, you do not believe in blind obedience. If yes, would the Eichmann defense be justified to excuse your acts.

Comment by Stan Beale — July 4, 2014 @ 1:44 pm

I suggest you read the section on disassociation again. Nobody is advocating blind obedience.

Comment by Jeff G — July 4, 2014 @ 2:34 pm

Can we create our own special Godwin’s Law, adapting it for Mormonism? As in, if folks bring up either priesthood ban or Mountain Meadows, they automatically lose the debate? Reductio ad sacerdotium prohibitum? Reductio ad mons prata?

Towns’ Law, perhaps, if not claimed already?

Comment by Michael Towns — July 4, 2014 @ 4:15 pm

Jeff G:

So is your argument that when faced with unrighteous dominion, “exit” is a legitimate strategy, but “voice” is not?

Comment by Nate W. — July 4, 2014 @ 5:39 pm

Jeff G, Your choices are too simplistic and limiting. Let me phrase my last question in your terms. Would you have left the church or grabbed your gun to go murder some men, women and children?

Comment by Stan Beale — July 4, 2014 @ 6:34 pm

Jeff G. You are missing an important choice. Let me explain. I was a Berkeley radical of the 1960’s. Contrary to the stereotype, there were many types of radicals. In my case, the thoughts of three men guided me; Henry David Thoreau, Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King. A simple summary of their ideas is that if something is fundamentally morally wrong, one must oppose it and try to change it. You may violate the law (church rule?, but if you do, you must accept the legal (church) consequences.

That is how you deal with a Mountain Meadows situation. Do not become a murderer. Do not leave the Church because of someone else’s failings.

Comment by Stan Beale — July 4, 2014 @ 7:19 pm

Jeff, I for one have no trouble following your reasoning and I agree. I’m a little surprised at the smoke an chaff meant to cloud the issues. Maybe I shouldn’t be. Ultimately it comes down to faith, not reason and incontrovertible evidence. As to those worried about abuses of power, there are enough checks and balances as far as I have seen.

Comment by DeepintheHeart — July 4, 2014 @ 8:43 pm

Stan and Nate,

There are two different ways of checking church authority in my model: that of the church and that of the world.

I would not say that we have no voice at all within the church. We do get to publicly object to some ordinations. We can meet with our leaders. Or we can disassociate from the church to the degree that we feel inspired to. But we do not get a voice regarding what others, including the church leaders, ought to be doing. (The mountain meadows falls in this category.)

Anything beyond that and we become part of the democratic world around us. This makes us a good and faithful democratic citizen but not at all a good saint. Hence the term, in the church but not of the church.

Comment by Jeff G — July 4, 2014 @ 10:10 pm

Jeff G I get it. If you did not murder innocent men women and children, you were not a good church member. That is dangerous sophistry of the nth order.

Comment by Stan Beale — July 5, 2014 @ 1:00 pm

Jeff, I think maybe your #28 goes a little too far in saying “we do not get a voice regarding what others, including the church leaders, ought to be doing”. I’m not familiar with Hirschman other than the Wikipedia article already cited; but why must the “voice” option be public? The “private voice” option exists, and I’ve used it frequently myself.

I can see the advantages to public expression of voice in a democracy where leaders of dubious integrity are supposed to be pressured into doing what’s right (with “right” being determined by the majority); but accepting the truth-claims of Mormonism entails taking it on faith that the leaders are sincere (if not always right), acknowledging that the Church is not a democracy, and understanding that it is God’s will, rather than the will of the majority, that must prevail.

Under the circumstances it strikes me that when we take our concerns public, we’re moving beyond “voice” and into “pressure”. That component of pressure indicates that ultimately, when it comes to divining the will of God, we are placing our collective faith in the caprices of the majority rather than the ability of the Church leadership to obtain revelation.

Comment by JimD — July 5, 2014 @ 1:07 pm

Stan, I think objecting to the MMM would fall into the category that Jeff labels “inactivity”–a label I’m not fond of, but the OP’s description of which seems applicable:

Comment by JimD — July 5, 2014 @ 1:14 pm

(Objecting at the time, I mean; in the sense of “refusing to participate when called upon to do so.)

Comment by JimD — July 5, 2014 @ 1:15 pm

Stan Beale (#29),

Actually, you clearly don’t get it. As JimD noted in #31, Jeff already addressed your point in the post. You should read more carefully next time.

Comment by Geoff J — July 5, 2014 @ 1:52 pm

Stan,

Good member or not, you would have made a terrible Isaac.

Jim,

You bring up some really good points that I think force at least two two revisions in my exposition:

1 voice – I’m all for voice so long as it does not chaff at or usurp leadership in any way that democratic principles call for. Thus, any voice that suggests some course of action other than that of the priesthood leader can only be at best a voice of human reason. Human reason is not only fine but morally encouraged from the perspective of the democratic world, but not the church. As long as these conditions hold, I don’t care what you call it.

2 inactivity – this forces a much deeper revision of my post, but to my point. I get extremely confused when I equate a lack of participation in the church with deviation from our leaders. I think a lack of participation is more whati was trying to isolate so as to suggest that an active member of the church is not at all the same thing as a faithful member of the church. Hence, the title. I would not, however, want to insist that all deviation from church instructions just is inactivity.

Comment by Jeff G — July 5, 2014 @ 3:12 pm

JeffG:

Regarding “voice”, there are clearly situations where even asking questions undermines authority.

The current leniency shown by church leadership in allowing people to question things has not always been the case, and certainly it could be argued that instances have arisen where there doesn’t need to be any discussion, but simple obedience shown.

“When the prophet speaks, the thinking has been done”.

I know this is an LDS context, but given the LDS church’s recognition that other churches also teach or have “truths”, does this dynamic also legitimately apply to them?

For example, the Catholic Church is about 60 times larger than the LDS church, in membership. It seems possible the Lord may try to shape things to His plan via inspiration given to the Pope.

Should Catholics adopt similar thinking?

(I know this introduces some complexity – no animosity conferred.)

Comment by MarkO — July 5, 2014 @ 7:49 pm

Jeff G:

I guess I’m confused with where you’re going here, especially with your # 34—are you claiming disobedience to a directive from a priesthood leader that one believes is wrong is OK, but openly questioning the directive is not? I guess I’m confused about what you’re saying.

Comment by Nate W. — July 5, 2014 @ 8:19 pm

“When the prophet speaks, the thinking has been done”

This old canard needs to be put to rest.

http://www.fairmormon.org/perspectives/publications/when-the-prophet-speaks-is-the-thinking-done

Comment by Michael Towns — July 5, 2014 @ 9:39 pm

MarkO,

We don’t believe the Catholics to have priesthood authority which makes us part of the world from their perspective, and like good democratic citizens we should feel free to check and balance their power by way of disconformation. And we can expect them to do the same to us since, to us, they are the world.

NateW,

That’s not too far off. Openly constraining and chaffing at church authorities are part and parcel for being a part of the world, not the kingdom. Yes, we can ask questions, express concerns, and so on, since that is part of living in the kingdom while having access to our own personal revelation. But we shouldn’t expect reasons to be all that forth coming veryoften, since our church is not guided by reason. Part of being part of a church that is led by god rather than man is that we are going to have lots of questions and concerns that don’t always have answers. That just is to have faith like Abraham.

But repeatedly asking questions and expressing concerns in front of the news cameras is something else. That is an attempt to check and balance church authority by the worlds way.

Thus, my model puts an immense amount of pressure on members to pray for confirmation of their leaders since our own understanding will never be sufficient. Once we start demanding reasons we have become part of the world.

Comment by Jeff G — July 5, 2014 @ 10:25 pm

Jeff G,

I love your stuff. (Though I confess that I’m confused at how little it seems people read but don’t actually read your posts)

Carry on.

Comment by Riley — July 5, 2014 @ 11:30 pm

I’m not that surprised really. I’m arguing for several things that are very much contrary to the moral intuitions which are taught us by the world. As such, I expect a certain amount of moral disgust and indignation that has very little to do with the actual arguments for or against it.

Comment by Jeff G — July 6, 2014 @ 8:39 am

Michael (#37),

Thanks for the link. That annoying old canard really does need to be put to rest for good.

Comment by Geoff J — July 6, 2014 @ 4:15 pm

In relation to “the annoying, old canard” which inadvertently found its way to publication in 1945, as indicated in Towns’ link, the more accurate statement attributed to Pres. Elaine Cannon in 1978, and supported by the First Presidency in 1979, is “When the Prophet speaks, the debate is over.”

See http://www.lds.org/ensign/1979/08/the-debate-is-over?lang=eng

Comment by Tiger — July 7, 2014 @ 4:50 pm

Touche’, Tiger.

Comment by Geoff J — July 7, 2014 @ 5:56 pm

I should note that Jeff is not backing away from the “When the Prophet speaks, the debate is over” idea at all. Rather he is embracing it wholeheartedly.

Also, saying “the debate is over” is less controversial than saying “the thinking has been done”. If the prophet is the mouthpiece of God on the earth then God’s answer would naturally end debates.

Comment by Geoff J — July 7, 2014 @ 6:01 pm

Geoff is absolutely right. If anything, I’m going even further than the quote by saying that when the prophet officially speaks, the thinking might not have been done at all, but the debate is still over. That’s just what it is for a church to be led by revelation in that sometimes we will be asked to do things for which exactly none of us know the reason. So, yes, I would definitely agree that “the debate is over” is much better than “the thinking has been done”.

Looking back at the original New Era article, I couldn’t help but notice that their point was almost exactly the one that I made in this post about sustaining vs objecting to our leaders and the lack of coercion.

Comment by Jeff G — July 7, 2014 @ 6:11 pm

I think it goes without saying that ending official debate on a matter is substantially different than ending thought on the same issue.

Comment by Michael Towns — July 8, 2014 @ 1:37 pm

I agree, but I’m not sure to what extent.

On the one hand, the official ending of debate regarding public policy is a bit of a misnomer since debate should not (ideally) be what determines policy. However, once revelation is received and an official decision made, then whatever conversation preceded the decision has come to an end. Any debate after the fact is an attempt at human reason constraining revelation rather than the other way around.

This, however, is not the same thing as an end to thought on the issue. On this front we are encouraged to continue thinking about anything and everything… but here is where I’m left to wonder. Thinking about some subjects upon which we have received revelation comes very close to, again, constraining our acceptance and allegiance to that revelation. There is thus a tension here that I feel is in some need of refinement and clarification.

Comment by Jeff G — July 8, 2014 @ 2:20 pm

Jeff G.,

I think I understand your position about legitimacy and authority and obedience.

For purposes of this discussion, let’s both assume that we agree that the right thing for members to do is to be obedient to leaders and have faith in their assessments.

The question I have is what percentage of disagreements does that resolve in terms of how good members behave.

You appear to think that it resolves a lot and I think it resolves very little.

Here is why. For the most part, people who are not obedient to leaders are not actively participating in church. They leave the church as soon as they can.

I believe most but not all of the differences of opinion of good members is a difference of opinion about what to be obedient to.

Most commandments and statements of the gospel use words whose meaning is different for different people. “prayer, spirit, love, obey, sustain, preside, honor, forgive, humble, etc.”

These are all words that are very hard to define across different groups of people.

Furthermore, many commandments create conflicting priorities and the specific action one should take to be obedient is not obvious.

Specifically, you are assuming that the values in conflict are from the world and informed buy the world’s standard of questioning.

But I think it goes deeper than that, in that the world informs both the meaning of words and of moral intuitions in a way that different people have different understandings of what is being requested for obedience.

You seem mainly to see these differences as acts of bad faith or belligerence rather than different understandings of what a person should be obedient to.

Furthermore, I believe that the most important parts of the gospel can never be expressed in such a way that it is clear what is being requested.

What does it mean to love?

Another way of saying this, is how can you be sure that a person who appears to not be being obedient to one particular commandment or request of leadership is not following an alternative one?

How do you that leaders never contradict themselves or make ambiguous statements?

One approach you use is to say that there are unique keys for each person. But who has the responsibility for example to determine if the president of the church is demented? Is it really clear? Who makes the judgment calls and how do they enforce them?

There are myriad other examples.

Comment by Martin James — July 8, 2014 @ 3:31 pm

“Another way of saying this, is how can you be sure that a person who appears to not be being obedient to one particular commandment or request of leadership is not following an alternative one?

How do you that leaders never contradict themselves or make ambiguous statements?

Is it really clear? Who makes the judgment calls and how do they enforce them?”

I would submit that this is where the gift of the Holy Ghost comes in very handy. Faithful members believe — and more to the point, experience — perceptions and feelings that go beyond simple emotional contrivance.

I’ve had experiences where the only way to describe what happened is how Joseph Smith described it as “pure intelligence” flowing into your heart and mind.

I don’t think I’m all that different from the typical, faithful Church member. In fact, I would say I’m on the low end of the spirituality spectrum. Yet I’ve had experiences where the Spirit was teaching me and it was supernal.

We probably, as Pres. Utchdorf has taught, live beneath our privileges in the regard. But, as trite as it really sounds to some, the Spirit does make the difference.

Comment by Michael Towns — July 8, 2014 @ 3:43 pm

Martin,

You bring up some really good questions which touch on many things that I have discussed in other posts.

First of all, I should confess that the members I am primarily talking about are those within the bloggernacle – a public space in which people who are not obedient to leaders most definitely are actively participating in church. For the most part, though, I think you are right.

Second, I object to your uncritically framing these issues in terms of what rather than who one believes and follows. This itself is a decision which the world wants to repress – again, in order to check and balance the power of authority figures. If we worry about what we should believe and follow, then, yes, things get complicated and vague… just like the world wants it to be. If we worry about who we should believe and follow, then things get simple and clear… just like the Lord wants it to be.

Finally, I absolutely agree that the meaning of such words can vary depending on the worldview from which you approach such words. This has been a primary concern within my posts in which I argue that individual interpretations of such words can usefully be grouped into two different camps – a grouping which this post largely takes for granted. The modern, democratic world around us teaches one way of interpreting, prioritizing and evaluating these words, while our pre-modern religious tradition has its own way of doing so. Despite the differences between these two traditions, however, I see the differences that exist within each tradition as being relatively small and benign.

Comment by Jeff G — July 8, 2014 @ 3:57 pm

I think the significant difference lies with whether we align our will with the Lord’s. We can think a matter all we want, but in the end, when a Prophet, (or a priesthood leader) speaks, do we forego all previous foolish notions to support him, or continue to deliberate an alternative? If we choose to support the Prophet (or a priesthood leader), whether we agree or not, then we ought to do all we can to understand the Lord’s will without undermining the Prophet’s/priesthood leader’s decree–regardless of church confirmation/association status.

Comment by Tiger — July 8, 2014 @ 3:59 pm

Tiger,

I’m not sure that I disagree with what you are actually saying so much as I disagree with your seeming resistance to clarification.

To say that we should not undermine a priesthood leader regardless of whether we associate with or confirm them seems like a step toward the wishy-washiness that Martin points to – a wishy-washiness that allows people to view themselves and their actions as righteous since it doesn’t clearly contradict any commandment. This wishy-washiness is exactly what I am taking aim at.

There are people in the bloggernacle who strongly associate with the church while at the same time undermining and disconfirming it. These are those who are in the church but of the democratic world which is getting very close to being a wolf in sheep’s clothing.

I see this vague wishy-washiness that I am trying to cut through as the only reason why people would ever be surprised or outraged at the events of the last month. These people are the targets of this post – people who see no difference between the morals and values of the world and those of the church. My hope is that by clearly articulating the difference which must exist between the values of the church and those of the world these people might better see – and hopefully second guess – their loyalties to the world.

Comment by Jeff G — July 8, 2014 @ 4:31 pm

Jeff G.,

But I think you are only looking at half the picture.

Authoritarian and hierarchical values are just as modern and worldly. The church is much more than a pre-modern authority institution.

For example, take Republicans. There is much in the current Republican tradition that mormons easily identify with that is worldly and pulls people away from the church. There is nothing small and benign about nationalism, for example. The church presents itself as a global religion and even in local Utah politics has made good treatment of immigrant in Utah, even illegal immigrants a matter of concern.

So, when people self-identify with a national or political ideal on authoritarian grounds that is at least as serious form of idol worship and putting other things above God, as is a modern, democratic ideal. Which authority matters as much as respect for authority in general. Since we know that the Gospel of Jesus preaches meekness and charity and peacemaking, to me both errors are equally significant; the “liberal” error of not respecting authority and “conservative” error of the worship of worldly tradition and power.

The liberals can do right for the wrong reason as easily as the conservatives can do wrong for the right reason.

Surely just in terms of sheer numbers, the greatest number of errors must come from the most common outlook: authoritarianism.

Isn’t is possible that you are focusing on the mote instead of the beam?

I understand you are trying to help people see the differences but I think the lack of adherence by the authority side to the commands of authority is at least as big a factor for those on the anti-authority side as is being actually anti-authority.

Comment by Martin James — July 10, 2014 @ 11:11 am

Martin,

I think you misunderstand me (which is likely my fault more than yours).

For example, I completely agree with this 100%:

“…to me both errors are equally significant; the “liberal” error of not respecting authority and “conservative” error of the worship of worldly tradition and power.”

The problem that I have focused on is that Mordernity teaches us to see all authority, without exception, as lacking any kind of intrinsic legitimacy. That, I think, is the biggest hurdle for the majority of people that would actually read an entire post of mine.

I suspect that once we acknowledge that some authority can be intrinsically legitimate, then the testimonies that most of the readers here truly have will largely take care of the rest. So, yes, you are absolutely right, but I think you and I are complimenting rather than contradicting each other.

Comment by Jeff G — July 10, 2014 @ 11:48 am