Anti-Intellectualism within Mormonism

I think we can all agree that within Mormonism there is a certain kind of ambivalence toward intellectualism, even if we aren’t quite able to put our finger on it. On the one hand, it seems clear that Mormonism embraces intelligence as such, going so far as to equate it with the Glory of God. Along these lines we are also told to seek truth and knowledge from the best books and counseled that to be learned is good so long as we don’t abandon the faith. On the other hand, there are at least as many passages which warn us of the learned and scholarly who preach the philosophies of men according to the understanding of the flesh. These tensions within the scriptures leave one wondering what place, if any, is to be found for intellectuals within the church.

The mirror image of this ambivalence within Mormonism towards intellectuals is a certain ambiguity in the term itself, for it is not at all clear who does and does not qualify as an intellectual. For example, in my experience “intellectual” is a term which is typically applied to others rather than oneself out of a sense of modesty. This would seem to suggest that the term designates somebody with exceptional intelligence or mental ability. There are, however, those who would call themselves an intellectual without any kind of immodest connotations. These people seem to think the word refers to anybody who enjoys or is drawn to mental activities such as reading, writing, arithmetic, etc. without any regard for the person’s abilities or talents in these activities. I would suggest that there is nothing in these definitions (mental ability or mental activity) which is contrary to Mormonism.

I would also resist any attempt to equate Mormon hostility toward intellectuals with a hostility toward certain kinds of mental content. To be sure, Mormonism is clearly hostile towards some beliefs and desires that are popular among intellectuals, but the antipathy which concerns us here is with the intellectuals as people, not the beliefs that those people happen to have. Furthermore, the scriptural warnings of which we speak are not aimed at “atheistic intellectuals” or “Darwinian intellectuals”, but are aimed at intellectuals as such. Accordingly, I suggest that Mormon opposition toward intellectuals has little to do with mental ability, mental activity or even mental content, per se. The church obviously does not want us to be stupid or ignorant. Furthermore, while the church also does not want us to hold certain beliefs which enjoy some popularity among intellectuals, it goes even further in not wanting us to be intellectuals in some deeper sense of the word.

Scriptural warnings against intellectuals are aimed not at mental ability, mental activity or even mental content, per se, but at mental hegemony. The church does not want us to be stupid or ignorant, but it does want itself to have the final word on certain subjects. (The same goes for every social group which seeks to reproduce its influence in the world, but at least the church is upfront about it.) Mormonism, then, is not against mental activity or mental ability, but the idea that the mind can/should be applied to – and in some sense have the last word on – any given subject. The mental hegemony of which I speak is not the claim that a person’s thoughts, words and deeds cannot be constrained at all, but is instead the claim that the only thing that can legitimately constrain them is the intellect, be it their own or somebody else’s.

At this point it is worth repeating that the intellectualism at issue here is not the supremacy of any individual person’s intellect, but the supremacy of the intellect as such. There is a huge difference between these two positions, for the first says that some person is beyond question while the second says that the only thing that can legitimately call a person or their thoughts, words and deeds into question is the intellect. In other words, a particular person’s gender, class, sexual orientation, social status, group membership or other such non-intellectual and non-universal attributes are, as such, irrelevant to an intellectual as far as justification goes. The only thing that justifies or legitimizes thoughts, words and deeds are the intellectual abilities and activities which we all possess.

The intellectual which is under attack in the scriptures is very similar to Alvin Gouldner’s portrayal of them a anybody who is imbued with the culture of critical discourse (CCD):

“[CCD] insists that any assertion – about anything, by anyone – is open to criticism and that, if challenged, no assertion can be defended by invoking someone’s authority. It forbids a reference to a speaker’s position in society (or reliance upon his personal character) in order to justify or refute his claims… Under the scrutiny of the culture of critical discourse, all claims to truth are in principle now equal, and traditional authorities are now stripped of their special right to define social reality… The CCD … demands the right to sit in judgment over all claims, regardless of who makes them…

“CCD requires that all speakers must be treated as sociologically equal in evaluating their speech. Considerations of race, class, sex, creed, wealth, or power in society may not be taken into account in judging a speaker’s contentions and a special effort is made to guard against their intrusion on critical judgment. The CCD, then, suspects that all traditional social differentiations may be subversive of reason and critical judgment and thus facilitate a critical examination of establishment claims. It distances intellectuals from them and prevents elite views from becoming an unchallenged, conventional wisdom.” (Against Fragmentation: The Origins of Marxism and the Sociology of Intellectuals, 30-31)

We are now in a position to understand scriptural hostility towards intellectuals a little better. The scriptures are not against us using our intellect nor are they against us having intelligence so long as these things are properly constrained(!). The scriptures are very much against our tendency to measure the gospel by intellectual standards such as empirical support or rational coherence. The gospel is under no obligation whatsoever to answer to our intellectual questions, nor is it in need of any kind of intellectual support. To the contrary, the gospel reserves the right to trump any thoughts, words or actions of our own, regardless of their intellectual merits. Thus, it is good to be intelligent and well-educated so long as we allow the gospel to constrain our intelligence and education rather than the other way around.

After thoughts:

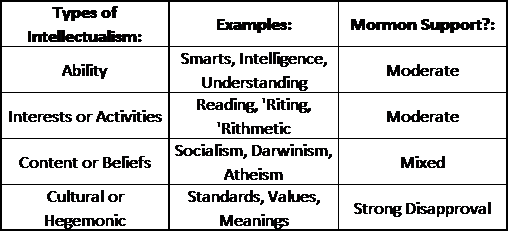

Having had a bit of time and feedback, I thought it might be nice to add a few thoughts. Here is a basic break down of the types of intellectualism which are considered in this post.

In the end, I suggest that the only intellectualism which Mormonism is consistently against is what I call cultural or hegemonic intellectualism. The church is clearly not against us being smart, nor it is against us seeking an education. What the church is against is the idea that our intellect and understanding have the final say with regards to what we believe, say and do. “I know not, save the Lord hath commanded me” is the epitome of this anti-intellectualism where we are encouraged to do things that make zero sense and find zero intellectual support within us.

Btw, any comment which does not actually engage the topic at hand will be deleted. Accordingly, rhetorical questions, off-hand proof texts and the like will have to be contextualized and specifically related to the point at issue.

Comment by Jeff G — October 31, 2013 @ 3:06 pm

I find you framing up a definition of intellectual here to be helpful. I am wondering if you can pass along some of the scriptural verses that you have in mind. I do find it a bit odd that there were no references to specific scriptures.

Comment by Eric Nielson — October 31, 2013 @ 7:00 pm

Good point. The post isn’t really about the scriptures, so I changed the title (again). I was sort of relying on a general feel of the scriptures, but I think appeals to specific scriptures would make for great comments.

Comment by Jeff G — October 31, 2013 @ 7:20 pm

I enjoyed your article. As one who, at times, meets both definitions you provide for one to be called an intellectual, it was a fun read. I do have two thoughts about your arguments…and it may just be that I’m reading a nuance that you didn’t intend, but I thought I’d share.

I do not believe that Church leaders would agree that the Church should have the final word. Just this last conference, President Uchtdorf pointed out that the mortal, imperfect leaders of the Church can and do make mistakes. I believe that what Church leaders want is for people who like to behave intellectually to keep their minds open to the possibility that they simply do not have or understand all of the relevant information to answer the question. Thus, when our mental abilities lead us to conclusions that are in conflict with Gospel teachings, intellectuals of faith should acknowledge that they may be missing part of the solution (by way of information or reasoning) and keep searching.

My second disagreement is a lexicological argument about your use of ‘constrain’ in your final line. The definition of constrain carries the connotation that the object is by its nature wild and uncontrollable–thus, in need of limits, restraints, etc. However, as you pointed out, the doctrine extols intelligence as the Glory of God. How can the Glory of God be, by its nature, wild and uncontrollable? I would submit that a better word here might be ‘guide’ or even ‘train.’ I would see this working much like a music teacher helps someone with natural musical abilities develop that talent, thereby setting it free. If the end goal is to become more like God, then we should not be doing anything that restricts or holds back our intellect–we should be setting it free in His way.

I also like your idea that the Gospel should be in the driver’s seat rather than the intellect. I think the use of ‘guide’ in place of ‘constrain’ preserves that good point you make.

Anyway…good article and there are my thoughts.

Comment by Bryan Embley — November 1, 2013 @ 8:11 am

Thanks for the thoughtful comments, Bryan.

1) Fallibility and open-mindedness are a sort of opium of the intellectuals within the church. Nobody says that a judge, a drill sergeant or a CEO are perfect, but they still get the last word within their proper domain. The scriptures say very little about open-mindedness, but have plenty to say regarding faith and commitment. In other words, yes, our leaders make mistakes and their decisions might be reversed, but this has nothing to do with us since it is not our place to correct them or anticipate changes on their part.

2) “we should not be doing anything that restricts or holds back our intellect–we should be setting it free in His way.” So is it constrained or not, then? There are plenty of anti-intellectual passages in the scriptures which show that our intellects ought to be constrained. Furthermore, in the same sense that telling somebody they’re totally free to do as we tell them means they aren’t totally free, so too saying our intellect is totally free to grow in God’s way means that it isn’t totally free. Whether this is a bad thing or not depends on whether you identify more with Mormonism or intellectualism.

Comment by Jeff G — November 1, 2013 @ 10:07 am

Jeff, will you define “the gospel” as used in the final paragraph?

Comment by Josh — November 1, 2013 @ 11:08 am

Gouldner attacks CCD because it doesn’t reverence authority, but I’m not really sure that Mormonism gives total reverence to authority either (excepting, of course, God’s authority).

The ultimate reason of why I, or any other Mormon who embraces Moroni 9:3-5, obey a prophet is not because of his authority, but because I received a spiritual witness that he has legitimate authority. This differs from Catholics, who reverance the pope because of an appeal to authority (his priestly lineage). Furthermore, beginning with Joseph Smith, we’re taught that we don’t have to accept a prophet’s authority on all topics, or even on all Mormon topics, but only when the prophet is speaking and acting like a prophet. And ultimately, the only way I can know that is through the spirit. So I’m not sure Goulding, based on that quote, would be fully satisfied with Mormonism.

Furthermore, Goulding points out that CCD doesn’t differentiate people based on wealth, sex, class, etc. when judging their words. But neither does Mormonism (sex being a possible exception in some cases). So long as a person is receiving revelation, what they say is as equally valid as what anyone else says, regardless of their background. The only difference between a deacon and a prophet in terms of receiving revelation is that we’re bound by the prophet’s revelation (if it’s intended for us), but not the deacon’s. God never tells us that he wouldn’t give us revelation for someone else, just that none of us will be held responsible for not following another person’s revelation, if that person is speaking outside of the hierarchy.

In other words, I think Goulding’s critique of CCD, based on this quote, could apply to Mormonism as well.

Comment by DavidF — November 1, 2013 @ 11:18 am

Oops, I switched Gouldner to Goulding half way through my comment. As you were.

Comment by DavidF — November 1, 2013 @ 11:19 am

Josh,

I simply meant religion as dictated by the Mormon faith.

David,

For starters, I should make it clear that Gouldner does NOT revere authority at all. He is very much a part of CCD and his efforts are aimed at making CCD more reflexive and self-aware. In other words, the fact that CCD is anti-authoritarian is a good thing from his perspective.

I also do not see anything that in my post that gives anybody “total” authority. Only an intellectual would think that if the intellect does not constrain authority, then nothing does.

To be sure, the decision as to whether we stay within the priesthood organization (aka the church) is a question of personal revelation. But once we have accepted the legitimacy of that priesthood organization, we have thus accepted the priesthood authority over us. I think a more honest take on scriptures such as Moroni (10) would say that while they can be used to support an anti-authoritarian view of religion, they do absolutely nothing to undermine a more authoritarian view. In other words, just because you think that verse supports you, doesn’t mean that it’s against me.

“So long as a person is receiving revelation, what they say is as equally valid as what anyone else says, regardless of their background.”

That is absolutely false, false and false. Mormonism is very clear that some people are not authorized to say certain things. They can privately think whatever they want, but public speech acts are very much regulated by the priesthood. Where did you get the idea that all people can with equal legitimacy speak on issues regardless of their priesthood position?

Comment by Jeff G — November 1, 2013 @ 12:15 pm

Last word? No, I think the historical and scriptorial ambivalence and caution is centered more around who do you choose to follow the Lord or the philosophies of men. Here you seem to be asking who are you going to follow, LDS leaders or the philosophies of men when those men may simply be engaging the position of LDS leaders with skeptical questioning for the purpose of determining if LDS leaders are actually representing the Lord’s will, for not everything they say does and in recent times they choose not to specify which does and which does not. Some of the more zellous choose to treat everything or nearly everything they say as if it were the word of God but we are cautioned against this too. Believing too little and believing too much is a mistake so it is in our best interest to study it out in our minds and ask God through the Spirit if it be so.

Comment by Howard — November 1, 2013 @ 12:29 pm

I’m not sure this has anything to do with what I said. There is a difference between what the Church authorizes a person to say, and what God may reveal to a person. I know of no church leader who has ever said that God won’t reveal something to a person who isn’t part of the office for which that revelation would normally go to. So to resurrect a dead horse, but for an entirely different purpose. The leadership doesn’t know why the priesthood ban happened. I don’t know either. But that doesn’t mean that God can’t reveal the answer to some other member. And if God reveals the answer to that person, then it’s a valid revelation. It doesn’t matter what his position in the hierarchy is, or whatever his background is. But I’m not bound by his revelation until I either get one, or the leadership gets one.

All people can equally receive revelation from God, but not all people are authorized to bind others by that revelation. Does the church tell people they can’t share their revelations with others? That’s news to me. All I know is that the church prohibits people from a. teaching revelation that undermines the church in a serious way, b. holding themselves out as an authority on revelation that the church doesn’t endorse, c. telling people that the church will re-embrace plural marriage in the future. But that has nothing to do with what I am talking about.

Comment by DavidF — November 1, 2013 @ 1:12 pm

I should add that I agree with a lot of your post. You point out that religion limits the scope of intellectualism. I agree. I’m concerned with something that, admittedly, skirts on what is relevant to this post (so I won’t push the issue). I think intellectualism serves a useful function in religion. Here are three big problems that arise with relying exclusively on the types of things that you’ve fit under the topic of religion:

1. Religion doesn’t always dictate the right moral answer. Scriptures and modern revelation don’t answer every moral problem I’m likely to run up against in my life.

For example, suppose I have a friend who calls me up and tells me that he’s going to beat up someone who I know who allegedly hurt my friend. What do the scriptures tell me I should do? I could make some arguments, but I don’t know if there’s a clear answer. Maybe this hypothetical doesn’t concern you, but I think the point it illustrates is still a valid one. I need an intellectual conclusion on a question that ostensibly rests within the category of religion.

2. Religion may misdirect me. A leader may hold a mistaken belief and teaches it to me, or I may follow a mistaken impression. That’s not to say that God misdirected me, but I’m in trouble if a religious leader misdirects me through a mistake of their own, and I have nothing outside of the topic of religion to verify their conclusion with.

For example, I once attended a YSA stake meeting where a visiting general authority said that even though he wasn’t preaching it as official policy, he thought it would be a really good idea if a couple didn’t have their first kiss until they were at the alter getting sealed. I think that’s a bad policy, but aside from saying it isn’t “official” (whatever that means), I can’t rebuttal that conclusion from other religious sources because no other religious source really addresses that topic, at least that I know of. And even if I do find one that contradicts him, his advice came after theirs, so I can’t invoke the intellectual tool of contradiction to dismiss his. It sounds like I’m stuck without intellectualism.

3. Religion may be responsibly appealed to on two sides of a moral debate, and religion doesn’t really help me decide which position to take.

Back when people were debating whether to pass Obamacare, I thought on the one hand, we have a responsibility to care for the poor, and Obamacare may be a good way to direct the government according to my religious beliefs. On the other hand, Obamacare seems like a bad thing, and I would make that argument based on agency, providential living, personal stewardship and so forth. In other words, I’m trying to decide whether I should support or oppose Obamacare on moral grounds, and my religion doesn’t give me the one, right answer, it gives me two answers. But surely one is more morally right than the other. I can’t solve the issue simply with intellectual reasoning, I need intellectual conclusions to determine a persuasive decision.

So even if there is a lot of religious arguments against intellectualism, religion can’t totally replace it, and in fact religion might cause harm if we don’t take steps to interpret it. And as soon as we start to interpret religion, we start making intellectual conclusions. I don’t know how you get around this, and I’m not sure that our scriptures or current authorities really help us figure these things out. Intellectualism may leave a lot to be desired, but I don’t think you can get away from it in reality. You’ve made a good argument, I’m just not sure it’s a useful one.

Comment by DavidF — November 1, 2013 @ 1:40 pm

Howard,

“those men may simply be engaging the position of LDS leaders with skeptical questioning for the purpose of determining if LDS leaders are actually representing the Lord’s will”

That’s exactly my point. This is a clear case of people thinking that the church and its leaders must somehow answer to the standards of intellectualism. This is the exact mindset that the scriptures reject.

I hope it’s clear that everything about your comment marginalizes the priesthood, but that’s not what this post was about. This post is about the kind of intellectualism that Mormonism rejects… and your comment is full of that as well.

Comment by Jeff G — November 1, 2013 @ 3:41 pm

David,

“There is a difference between what the Church authorizes a person to say, and what God may reveal to a person.”

Absolutely. That was my point when you said that “what they say is as equally valid as what anyone else says, regardless of their background”. People can receive personal revelation to their hearts delight, but since it’s personal I should never know anything about that. In other words, from the church’s perspective your having received personal revelation on any subject is exactly the same as your having received no personal revelation. Your personal revelation carries no weight and thus should never be brought up in church, blogs, etc.

“Does the church tell people they can’t share their revelations with others? That’s news to me.”

Sure, it can be brought up as a kind of faith promoting experience, but the content of that revelation carries zero legitimacy at all and for that reason should not be brought up in most contexts. That’s what it means to be “bound by someon’es revelation”, that it carries legitimacy. We are not bound by other people’s personal revelation which means that their revelation has zero legitimacy. We cannot justify our words and actions to others in terms of personal revelation. That’s what makes it “personal”.

Comment by Jeff G — November 1, 2013 @ 3:48 pm

David again,

I agree that all of these topics are connected to, but not really at issue in this post. This was the first in a series of posts by which I mean to expand on the Trojan Horses post over at M*, so rest assured that I’ll get to these topics in time.

1) I think you need to say a lot more if you’re going to argue from “religion doesn’t tell us everything” to “we need intellectualism”. A lot more. Why would you suggest that intellectualism in the only tool we have to deal with those situations?

2) “I have nothing outside of the topic of religion to verify their conclusion with.” Again, why do you assume that? “It sounds like I’m stuck without intellectualism.” More like you’re stuck with just moving on with your life and not worrying about the subject at all since it’s not binding (aka not legitimate).

3) “So even if there is a lot of religious arguments against intellectualism, religion can’t totally replace it” Where did this come from? The church doesn’t even try have the final word on most subjects in our lives, nor does anything in my post suggest otherwise. “And as soon as we start to interpret religion, we start making intellectual conclusions.” Whatever “intellectual” means in this context, it sure isn’t “intellectual hegemony”. There is nothing in the world which forces us to construe all speech acts in terms of arguments with premises, conclusions. This is nothing but an intellectual article of faith which is rightly rejected by scriptures.

Comment by Jeff G — November 1, 2013 @ 3:59 pm

Jeff G wrote: This post is about the kind of intellectualism that Mormonism rejects… and your comment is full of that as well. So your saying skeptical questioning is rejected by LDS Mormonism even for the purpose of decernment?

You seem to be attempting somewhat unsuccessfully to construct an argument that LDS leaders cannot be faithfully questioned via reason and therefore must be followed without question. I reject this. How do you support it?

Comment by Howard — November 1, 2013 @ 4:16 pm

You’re getting closer to my point.

In the same way that a judge, CEO or drill sergeant gets the last word, and what they say goes no matter what the arguments for or against them, so too are things within the church with our priesthood leaders.

You can privately question whatever you want, but sharing complaints and criticisms out loud amounts to insubordination/contempt/apostasy. No judge, CEO or drill sergeant is infallible, nor do they claim to be. Similarly, people are free to privately disagree with that judge, CEO or drill sergeant without reprisal. But having their judgment, decisions and orders questioned out loud are totally out of bounds. That is the kind of intellectualism that the scriptures are clearly against.

Comment by Jeff G — November 1, 2013 @ 4:28 pm

1.

Well, I was trying to go by your definitions for intellectualism and religion, but maybe I’m confused. In the context of dealing with moral or spiritual issues, I thought that we could either rely on religion or on intellectualism. So if religion can’t answer an issue, and we have to grapple with that issue, then all that’s left is intellectualism. What did I miss?

2. Alright, for argument’s sake, let me modify the situation. Suppose the leader neglected to mention that his position wasn’t official. How would I determine that I wasn’t bound by it if I didn’t draw an intellectual conclusion? (feel free to answer this one in the follow up post you’re planning). In other words, I think it’s easy to dismiss the example, but it’s a little bit harder to dismiss the point I’m trying to illustrate with it.

3. I’m lost here. I thought I understood the broad topics of religion and intellectualism, but now we’re talking about the church and intellectual hegemony. As I understand it, we’re supposed to use our religion to help us answer moral dilemmas, like whether to morally support Obamacare (or whatever). If my religion supports both sides, then I can’t make a moral decision, so I have to rely on intellectual conclusions to make a moral decision. But the second I rely on intellectual conclusions, I’ve replace religion with intellectualism as the vehicle for making a moral decision, and thus place intellectualism over religion. I thought that you were against that kind of result. Clearly, I’m having a tough time pinning down your definitions.

Comment by DavidF — November 1, 2013 @ 4:36 pm

1) Well, I was focused on a power struggle between two cultures, with the main point being that official statement are allowed to supersede, trump or correct our own intellect, but not the other way around. I didn’t have much anything to say about what we do in each and every situation.

2) “How would I determine that I wasn’t bound by it if I didn’t draw an intellectual conclusion?” Easy, ask a duly authorized priesthood leader. The one way which is absolutely forbidden throughout the scriptures is to publicly marshal arguments with other people for and against the proposition. That is the intellectualism which is totally out of bounds.

3) I have to say, I’m lost on this one. The post is about how priesthood authority trumps intellectual arguments and not the other way around. The church typically doesn’t get involved in politics, and when it does it’s pretty obvious which way we are supposed to vote. I’m not terribly interested in anything beyond that.

Comment by Jeff G — November 1, 2013 @ 5:28 pm

Put another way, Mormonism is perfectly willing to grant a degree of legitimacy to arguments and criticism, so long as we grant the official statements of priesthood leaders even MORE legitimacy.

Comment by Jeff G — November 1, 2013 @ 6:21 pm

Sorry Howard, but I had to delete your comment. You’ll have to do more than drop a proof-text that we’ve all read a hundred times and pretend like that moves the conversation forward in any way.

Comment by Jeff G — November 2, 2013 @ 10:53 am

Jeff,

Okay, this was where I think I was confused (and still might be). In other words, you’re not necessarily against intellectualism addressing moral topics, or even church related topics. What you’re against is putting intellectualism above the church in cases where the two clearly clash. Is that right?

Comment by DavidF — November 2, 2013 @ 11:27 am

Whoops! Try again Howard!

The passage you quoted had no obvious connection to the post and you didn’t bother to articulate the relevance. I’ll respond to your comments once they actually respond to the post.

Comment by Jeff G — November 2, 2013 @ 12:01 pm

David,

You’r pretty close. Again, the intellectualism which I suggest the scriptures are warning us against isn’t any kind of intellectual ability (skill is logic, inference, etc.) or any kind of intellectual activity (logic, argumentation, etc.). Thus, I don’t think the scriptures are necessarily against moral reasoning (although I still see no reason to think that this is all we are left with once we’ve exhausted the scriptures).

The intellectualism which I think it does reject is that which thinks that reason stands above and is supposed to evaluate everything, including moral and church related topics. It is the intellectualism which thinks it has the right to call religious bias a bad thing, which thinks that censorship of any topic or believing anything that “doesn’t make sense” is automatically bad, that thinks we should follow the strongest argument wherever it might lead. This is the hegemony of the intellect of which I speak. It’s the idea that the entire world and all the social phenomena in it are to be evaluated by intellectual criteria.

The reasoning of man (intellectualism as ability or activity) can be very good and useful for some things so long as we don’t think that it can or ought to be applied to matters of faith. If there is a conflict between a position which is supported by persuasive arguments and a position which is supported by religious authority, the latter is always supposed to win. This is something that no intellectual worthy of the name would ever tolerate.

Comment by Jeff G — November 2, 2013 @ 12:26 pm

I think a part of the problem stems from the fact that an intellectual will likely have a difficult time disentangling these different versions of intellectualism. To repeat, there were 4 versions which I considered:

1) Intellectualism as ability (being smart)

2) Intellectualism as interests (reading, writing)

3) Intellectualism as content (popular beliefs among intellectuals)

4) Intellectualism as culture (rules for assigning legitimacy)

I suggest that the scriptures are not anti-(1) or (2) and that they condemn more than just (3). Rather, I locate the anti-intellectualism in Mormonism at (4).

Intellectuals will have a hard time seeing a difference between these categories depending on how strongly they have embraced (4). Once they evaluate the entire world in terms of intellectual values, then an intellectual person just is one with the ability to perform well according to the rules of (4) and is thus legitimized by (4). An intellectual activity just is an activity which is highly valued within (4) and therefore carries some legitimacy. An intellectual beliefs just is a belief which is (for the time being) legitimized within (4).

Thus, the culture of intellectuals will evaluate and legitimize most things differently. For instance, certain abilities (1) will be prioritized differently by intellectuals than they will be by the prophets. Certain activities (2) and beliefs (3) will also be prioritized differently. But just because being smart (1), well-read (2) and a socialist (3) might be strongly legitimized within (4), this does not necessarily mean they are altogether illegitimate or immoral within some other culture, such as Mormonism. What is bad or illegitimate within Mormonism, however, is thinking that (4) is or ought to be the ultimate source of or standard for legitimacy in the world. The sin lies not in being smart, well-read or socialist, but in evaluating and prioritizing these things according to the standards of the intellectuals rather than the prophets.

Comment by Jeff G — November 2, 2013 @ 12:39 pm

For the record, I really appreciate your pointing out which parts of my position are unclear and forcing me to repackage it. There is quite a bit of subtlety to it, but I think it’s pretty easy to accept once it clicks into place. The trouble is getting it to click in just the right way – and that’s my job.

Comment by Jeff G — November 2, 2013 @ 1:16 pm

It’s hard to become as a little child when you intellectualize. Just as much of ancient Israel would rather die than look at the bronze serpent, because “it can’t be that simple”, we often feel the need to complexify gospel teachings.

In the end, the gospel is more about heart than mind. The mind should not block the heart, even if the mind is wrong. If you can intellectualize love and forgiveness, more power to you. Just remember this is the stuff primary children understand.

Comment by Bradley — November 2, 2013 @ 8:41 pm

No problem. I think your argument is getting more forceful. Where I diverge is that I’m not convinced that there aren’t exceptions to the position you’ve laid out. Meaning, the scriptures clearly put prophetic authority over intellectual authority, but there are historical examples of where prophetic authority has shown cracks; that is, sometimes a prophet gets things wrong. Our church hasn’t really developed any good mechanisms for recognizing if/when that happens, and what to do about it. Hopefully you’ll address this in future posts.

Comment by DavidF — November 3, 2013 @ 3:38 pm

I’m not sure that I will say all that much more about it, actually. Who’s standards are being used to measure the wrongness of the prophets and the goodness of the corrective mechanism? It seems to me like the prophets have done just fine by their standards even if they haven’t lived up to other peoples expectations.

Comment by Jeff G — November 3, 2013 @ 5:13 pm

Maybe. Consider the General Authority debate on evolution. James E. Talmage argued that evolution was okay with the Gospel. Joseph Fielding Smith said it was inconsistent with the Gospel. Eventually Talmage died and Smith maintained his position. Elder Nelson has also spoken against evolution. In general, though, the First Presidency has stated that the church doesn’t have an official position on the topic.

Clearly if a hypothetical member, John, knew all this, he would know that he wasn’t bound. But consider these hypotheticals:

A. John is living at the time of the Talmage/Smith debate, but before the First Presidency statement. What should he believe?

B. Same circumstances except that John had only ever heard Smith’s side.

C. John is living a couple decades later, knows Talmage and Smith disagreed, but also knows that since Talmage died, Smith has held to his position. John doesn’t know about the Statement.

D. John doesn’t know anything about the debate or the First Presidency Statement, but has heard Elder Nelson speak negatively about evolution in General Conference.

It would be nice if John went online and did research to find all the facts, but in at least some of these hypotheticals, he didn’t have that opportunity, and if John lives in an internet age, if he’s a standard member, he might never think that he should find out if there’s more to the topic than Smith’s or Nelson’s discussions on the topic. Most members wouldn’t necessarily question the issue to find out more, and they do that in part because prophetic authority is always taken as final.

I take it as a share assumption that we agree that John is best served by knowing the truth; that is, there is no official church position. But if John strictly follows prophetic authority, he may (a) never research beyond a Nelson/Smith statement, and (b) may end up believing that evolution is inconsistent with the church when in fact it may not be.

Of course, you could say that what does it matter; this issue isn’t a big deal, but John’s testimony may rest on the line because he can’t reconcile scientific evidence with a church claim that may not even be true (i.e. that evolution contradicts Mormonism). John’s dilemma isn’t that evolution is tough to reconcile with Mormonism, but that in following the prophetic standard, he is being led to a conclusion that is possibly false and may lead him away from the church. Here, intellectualism and religion butt heads, but the religious position John takes is wrong, and it could contribute to his loss of testimony.

Comment by DavidF — November 4, 2013 @ 10:00 am

A better example, though more trivial, is that Joseph Fielding Smith adamantly maintained that Paul wrote Hebrews. There is almost no good reason to believe that Paul wrote Hebrews aside from the fact that Smith adamantly believed it. Smith, when stating this, cited this reference from Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith:

Fielding Smith was a very literal reader, so you could see where he thought that Joseph’s statement is Gospel proof that Paul wrote Hebrews. Personally, I think that Joseph was making an off handed statement. But under the prophetic authority standard that you’ve advocated, I probably shouldn’t disagree with Joseph’s statement, and I almost certainly shouldn’t disagree with Fielding Smith’s statement, because Fielding Smith was adamant that Paul wrote Hebrews, and Fielding Smith was a prophet (or at least an apostle when he claimed this first, but maybe that doesn’t matter).

There are other good examples I could cite. Another off the top of my head: BYU professors have argued that Fielding Smith and others were wrong about the location of the Hill Cumorah. Are they on the high road to apostasy?

The point is, I think your basic argument is right, but there seems to be some good exceptions to the rule.

Comment by DavidF — November 4, 2013 @ 10:25 am

I don’t think there is really all that much ambivalence with regard to “intellectualism” within the church. The LDS leaders have been very clear that we should be seeking after knowledge, they put their money where their mouth is by heavily investing in education both within and outside the US (the source of the bulk of the church’s money).

Where “intellectuals” typically get it wrong, and where (IMO) both the Church and the Scriptures warn against is when the intellectual crosses into boundaries over what I like to call over-certainty. If you look into the academic or professional worlds that are notably full of “intellectuals”, one thing we find through objective measure is that there is a complete and wide-spread problem with over-certainty. It pollutes opinions of all ranges, from anthropogenic global warming, to vaccines, to detailing the usefulness of FMRI results. Where the church members get themselves into trouble, is when these things in which “intellectuals” believe there is a level of rigor and authority the members start to treat them as authoritative. I believe your response to David about whether or not the prophets have “gotten things wrong” is appropriate. Who is measuring what and why it was wrong?

One example that has been discusses here on this blog heavily was blacks receiving the priesthood. The detractors will say the prophets “had it wrong”, which from one myopic view is probably correct. Other members will have other things to say, like how many prophets had personal desires to relieve the ban, but couldn’t, which suggests despite not changing things that prophet “had it right” according to the detractors criteria of being right but were unable to change things. Others might point to the fact that the scriptures allude to an idea that the privilege of holding the priesthood was revoked with a semi-specific end-game..and once that end game was completed the privilege would be restored to the seed of those originally affected by the revocation. If that last statement is even partially right, then the intellectuals that have measured an action by church leaders as “wrong” is irrelevant….even if they don’t want it to be seen as such since the very nature of someone labeling themselves as an intellectual has to do with having a view as to what is qualitatively right, wrong, good, bad etc.

The point isn’t to talk about that specific thing, the over arching point that I’m making is that “right and wrong” is by and large a useless measure of things since without proper and equal context it’s impossible to measure. That is the major danger with “intellectualism”, that despite having a obviously incomplete set of information from which to draw conclusions people arrive at decisions that are over-certain to the point of deciding moral designations such as “right and wrong”.

That is a dangerous game.

Comment by Scott — November 4, 2013 @ 12:29 pm

David,

I’m not seeing the force of you objection. I think we both agree that if we contrived a similar case within academia, this would hardly be reason enough for scholars to embrace religion.

Yes, there are practical difficulties in figuring out exactly which statement are backed by priesthood authority and binding upon believers. All the same, it is clear that some statements definitely are and some definitely aren’t. There will always be penumbral cases.

Further complicating things is the fact that Mormonism is under no obligation to remain entirely consistent across space or time. It is perfectly acceptable for later revelation to contradict and overturn past revelation without thereby disavowing the legitimacy that the past revelation once carried.

Comment by Jeff G — November 4, 2013 @ 1:39 pm

Scott,

I think you and I are pretty close to each other here. I would only add that I think their over-uncertainty of intellectuals is just as dangerous and even more widespread. But I think that all of these really just boil down to the fact that intellectuals gauge and evaluate speech acts by different standards than the prophets do.

Comment by Jeff G — November 4, 2013 @ 1:43 pm

Not really. The way knowledge comes about in academia is entirely different. If a prophet is potentially wrong, there is virtually no way to assess his truth claim within the realm of Mormonism. Academia has other options.

Though, I actually follow Montaigne in thinking that academic learning should lead us towards faith. One point you’ve brought up consistently in these posts, but haven’t really brought both barrels on is that intellectuals are often unaware of the limits of reason and science. Montaigne used skepticism to show that human understanding is intensely limited, and so we ought to have faith in a being that knows better, i.e. God. But that’s neither here nor there.

Clear to whom? Not everyone. I once tragically and unintentionally made an old college roommate cry when I showed him that different church leaders hold different ideas about God’s foreknowledge. And in my experience, he isn’t atypical in terms of accepting whatever a prophet says as totally divine.

Of course, he could have easily reconciled the contradictory statements by pointing out, as you have, that the latest prophet’s word trumps any earlier ones.

That might be useful policy on some issues, but when we’re asking if God has absolute foreknowledge, the answer can’t be “no” and then “yes” simply because one revelatory authority contradicts an earlier one. You can’t say that both were right at different times on the one hand, and on the other hand say that truth is things as they were, as they are, and as they will be.

Objectively speaking, my roommate should have never have had a problem with irreconcilable statements from different leaders. He should have done his research. But what kind of incentive would he have had to research the issue if (which he didn’t) if he assumed that a prophet’s word is always final? In fact, the reason that you or I can say that it is clear that Fielding Smith’s views on Pauline authorship, is because I didn’t think he was right! If I simply accepted what he said, then there would be no reason for either of us to believe otherwise (since we should exclude intellectual conclusions), and we both be believing something that the great body of intellectual evidence contradicts, but with no real justification since we didn’t actually get our beliefs from a divine source.

Since you point out that the latest prophet trumps all previous once, and no intellectual argument may contradict the latest prophet’s teachings, can we ever legitimately question something a prophet said unless it is somehow clear that he is not acting as a prophet? I see nothing in the scriptures nor in the words of modern day prophets that should carry us to this extreme.

Comment by DavidF — November 4, 2013 @ 4:35 pm

“If a prophet is potentially wrong, there is virtually no way to assess his truth claim within the realm of Mormonism.”

But this somewhat begs the question, for “assessment” is something which is priced much more highly within intellectual circles (which is why the intellectual is so worried about blind obedience). If we ask how people ought to respond to prophetic statements, we must specific which people (and this also aggravates the intellectual). Within Mormonism, priesthood authority is vetted by people of equal or higher priesthood authority. Even the most shallow reading of Mormon history will provide several examples of this at work.

If we ask how we are to assess the prophets, the answer is that we aren’t. This is exactly what the condemnation of intellectuals boils down to. We can privately come to our priesthood leaders to express our doubts. We can privately pray about whatever issues we might have. And then we are free to sustain or not sustain the priesthood.

Academia doesn’t necessarily have more options than religion so much as it prioritizes its options differently. Within religion authority, tradition and prophecy mean an awful lot, whereas they mean very little within intellectual circles. The latter prefer empirical data and rational analysis while the former doesn’t care too much about these things.

“You can’t say that both were right at different times on the one hand, and on the other hand say that truth is things as they were, as they are, and as they will be.”

This is certainly getting at the heart of my position. I think the motivating point of that passage is that we can trust God and His counsel no matter where or when you are to get us to the single, unchanging truth which we all seek at the end of our respective journeys. What seems clear to me is that the scriptures clearly do not advocate some kind of correspondence theory of truth where prophetic statement are accurate depictions of an unchanging eternity.

“One point you’ve brought up consistently in these posts, but haven’t really brought both barrels on is that intellectuals are often unaware of the limits of reason and science. Montaigne used skepticism to show that human understanding is intensely limited, and so we ought to have faith in a being that knows better, i.e. God. ”

I most definitely do NOT agree with this approach. Yes, I agree that the intellect is limited, but when we rely on the intellect to demonstrate this we are tacitly acknowledging that, limited though our intellect might be, it’s still the overriding set of principles by which we ought to live. I do not agree with this. Yes, the intellect is the best we have for many purposes, but not all and it most certainly does not have the right to asymmetrically pass judgement on other mental tools. Thus, I’m not trying to highlight the limited nature of the intellect, but rather the plurality of mental tools by which we are able to navigate the world around us.

“Objectively speaking, my roommate should have never have had a problem with irreconcilable statements from different leaders. He should have done his research.”

Again, this is exactly what I’m arguing against. An intellectual problem was raised, and it is automatically assumed that there must be an intellectual solution to that problem. You are suggesting that if your roommate would have just applied the evaluative principles of the intellectuals they would have been okay. That to me is the problem, not the solution. The problem is that it is assumed that intellectual principles have some kind of unique and rightful place in these matters, when they simply do not.

Comment by Jeff G — November 4, 2013 @ 5:09 pm

David,

Here is where I can point out a great example of where over-certainty can creep into “intellectual” discussions. It’s clear that a logical statement is being made X can’t be true. The clear problem now, is determining (and agreeing upon) the set of premises that must be in place for that logical statement to have any sort of meaning at all. The entire statement hinges upon what definition of absolute we are going to employ. If we go with the definition that sort of connotes completeness, then yes, absolute knowledge can be one set of things today and tomorrow be different without ever being incomplete. If we choose the definition that connotes more perfection than anything, than most certainly perfect knowledge today can be different than perfect knowledge tomorrow.

Perhaps, when those prophets (though probably not speaking authoritatively at any of the given cited references) have what appears to be a disagreement or a statement that is incongruous to others what we likely have are two people speaking with differing views of the premise, but making logical conclusions that seem to contradict each other.

Your roommate that you made cry may not understand the nuance of logic, he may not understand that there isn’t a single definition for the word absolute, he may not even have the intellectual capacity to understand those things even if he was exposed to them and tried to research them exhaustively.

In that case, it would seem at as long as the church member derives their knowledge from the official canon and statements of the church they would indeed still be assessing the truth of the prophetic claims to the best of their ability, but still rightfully yielding to prophetic authority as well.

Where people typically get in the weeds with these types of discussions is when their source material is less than official stances. It was something that was overheard at a lecture, dictated by one person, recorded by another and transcribed and compiled into a book by another. It may be accurate, it may not, I have no idea…..but I’m 100% confident that there is an uncertainty in those types of statements and source literature that doesn’t (assuming of course the prophetic authority exists, which I understand not all do) exist with the clear distinctions of when the prophets are speaking prophetically, and in their official capacity as witnesses of Christ.

Comment by Scott — November 5, 2013 @ 6:34 am

It is easier to reconcile by understanding that truth is that which leads to God, shaping us to become life Him. What leads one generation to Him is not necessary what leads another generation, else we would all be invading our neighbors like the Israelites, or sacrificing our sons like Abraham, or leaving our homes and traveling across the ocean like Nephi.

It isn’t the details which are important, it is principles such as sacrifice, obedience to God, consecration, submission, humility, charity.

Don’t confuse the need to travel different directions for the unified destination.

Comment by SilverRain — November 5, 2013 @ 6:54 am

*like Him

Comment by SilverRain — November 5, 2013 @ 6:55 am

Regarding Mormon ambivalence toward intellectualism, a 2007 church news release offers clarification:

Comment by Howard — November 5, 2013 @ 8:13 am

Great comment, Scott. I really enjoyed that. You make in good point in that while religious people do take certain things to be beyond doubt and while intellectuals do that those religious things to be questionable, like any culture, they must take some set of beliefs to be beyond question.

SilverRain, I really enjoyed your comment too. I past posts I tried to argue that religion and science interpret the word truth to mean very different things. Theology, in my opinion, happens when religious people buy into and take too seriously the scientific interpretation of truth.

Howard, very nice pull. I see that release as being very much in harmony with what I have in mind. (I think think the intellectuality which is encouraged lies squarely in the ability/activity realms.

Comment by Jeff G — November 5, 2013 @ 11:52 am

Jeff G,

You seem to be dodging around my arguments, but maybe we’re just speaking past each other. There’s a lot I could quibble about, but the core disagreement seems to revolve around this paragraph:

I’m not sure I understand what you’re saying. If I understand you correctly, you are saying that we shouldn’t assume that a prophet’s statement accurately depicts an unchanging truth, but we should trust that all prophets’ statements are going to lead us to the grand eternal truths. Is that fair?

There are two problems with this position. First, I do agree that not every prophetic statement reveals an unchanging divine truth. I think a good example of what you are talking about is the evolution of afterlife doctrine. In the Bible, the afterlife was simple heaven and hell, but Joseph Smith gave us a more complex, vivid description of the afterlife. In one sense he contradicted the Biblical doctrine, but in another sense he merely took a “lower” truth and raised it to a “higher” truth. He gave us a truth that more appropriately reflects the afterlife.

However, in the hypothetical I raised, where one prophet advocated God’s limited foreknowledge, and the other contradicted him, there is no progression from a “lower” truth to a “higher” truth, like we see in the afterlife doctrine. Instead, this is an example of pure contradiction. The second position doesn’t expand, tweak, clarify, or even maintain any part of the first position. It completely contradicts the first one. Did God reveal a doctrine that was true then, but is now not true? I don’t think you can say that about God’s foreknowledge. Did God reveal a doctrine that wasn’t true but did it anyway because it would lead people to Him? If you suggest that, then you’re advocating a very different God and religion than I read in the scriptures.

Second, you still haven’t shown how a person can tell when a prophet is making a prophetic statement, or making a statement that isn’t prophetic. In the Pauline authorship point I brought up, you said that Fielding Smith’s statement was clearly not definitively divine. How could you know that was true? When you start assessing language to determine whether a comment was divinely inspired or not, you begin to assess the validity of a prophet’s statement through literary analysis. And if literary analysis is your guide for determining what’s divine, you’ve accepted an intellectualist position.

On the other hand, if you can’t make a literary analysis to determine a prophetic statement, then how could you or anyone else ever know if a prophet was wrong about something? Any time a prophet speaks, it’s possible that he is sharing a revelation. And if I can’t use some external tool to assess his statement with, then I must assume that any statement he makes is revelatory. If I assume otherwise, I’m an intellectualist.

Comment by DavidF — November 5, 2013 @ 6:56 pm

Scott, I’ve never heard anyone share your second definition for “absolute”. It appears to me that you’ve added an idiosyncratic definition (which is ironic, given the word in question). You’ve got an interesting argument, but it hinges on a definition that I have no reason to accept.

Comment by DavidF — November 5, 2013 @ 6:57 pm

SilverRain, I broadly agree with your post, but it seems a little too overgeneralized. For example, consider slavery in the Old Testament. The Israelites are told what to do about their slaves, which implies slavery is okay, but as you know, God condemns it now. Personally, I think that God doesn’t like slavery, never has, and never will, but He allows people to do things He doesn’t like while He works on bigger things, like faith.

But let’s plug in slavery into the position you’ve outlined. I choose slavery, because it’s a good example of something that was once part of our ancient religion, but isn’t now, and so some people could argue that there is a contradiction in revelation, but perhaps God was merely commanding whatever leads people to HIm. So I could argue that God commanded slavery in Old Testament times because it helped lead the Israelites to Him (otherwise why would He)? But God condemns slavery now because it helps lead us to Him (otherwise why would He)?

Do you agree with this explanation for divinely instituted and retracted slavery? If you do, then I think we have different ideas of what it means for God to be moral. But if you don’t, then perhaps you agree with me that sometimes God allows his prophets (here: Moses) to have mistaken moral values, such as the belief that slavery is okay.

If you believe, like I do, that God allows prophets to have mistaken moral values, and then a later prophet contradicts an earlier prophet’s moral value, then we have evidence showing that the earlier prophet held a mistaken moral value. He is still a prophet, not because he had a perfect moral record, but because God works with what He’s got. Is that fair?

There’s another reason why I think your comment is generally right, but too broadly construed. As you point out, if two prophets from two different time periods share inconsistent revelations, God may be the author of both, because circumstances demand two different revelations. But what if two different prophets preach two contradictory views about the Gospel, and the two of them live at the same time? That scenario doesn’t fit very well with what you’re saying.

In short, I agree with you, but I don’t think your explanation fits every disagreement between prophets, and so we’ve got to figure out what to do with the ones that don’t work with your explanation.

Comment by DavidF — November 5, 2013 @ 7:08 pm

I can neither agree nor disagree, because your phrasing betrays some fundamental assumptions of yours that I simply can’t address at this time. It’s just more complicated than fits for a blog comment Swyped on a phone….

Comment by SilverRain — November 5, 2013 @ 7:20 pm

David,

http://www.thefreedictionary.com/absolute

I can’t opine as to whether or not that is sufficiently defined for you to accept at as more than an idiosyncratic definition…..but according to them it’s the most likely definition.

This is the very danger of the over-certainty problem. In this case you’ve eliminated the ability for us to have a real, intellectual discussion because you completely rejected the premise. The impetus of that rejection was due to your certainty of how the word absolute should be defined, even though many people allow for the rejected definition.

I mean that you’ve eliminated the ability for that discussion to flow in our hypothetical discussion where we are dissecting the logical statement of X can’t be true. I just want to be clear that I’m not saying you’ve ruined this discussion. :)

To address your other comment about slavery:

I don’t get what you’re saying about slavery, and God’s morality at all. It would be helpful if you’d expand it a bit.

Comment by Scott — November 6, 2013 @ 8:10 am

Scott,

I’m referring to your second definition: “more perfection than anything”, which doesn’t imply perfection or completeness, but just that something is a little more complete or perfect than anything else that you would compare it to. This (your) definition isn’t supported by thefreedictionary, nor have I ever heard it until you raised it. You have to make a persuasive claim as to why I should accept a new definition to a word that no one else uses. Also, I’m not exactly sure how the word absolute factors into the discussion.

The point of my slavery argument was to show that SilverRain’s comment has exceptions to it. The question is: if one prophet decrees something, and a later prophet makes a contradictory claim, did the first prophet make a mistake?

SilverRain points out that God may give two prophets contradictory revelations if it serves His purposes. Thus, both prophets decreed rightly.

But what happens when one prophet decrees a law that enshrines slavery in the religious code, and then a later prophet says slavery is against the law of God? Can both be right within their circumstantial time frames?

I don’t think so. I think when you start saying that God will sometimes uphold slavery, you travel down a slippery slope saying God has a changeable morality. I don’t think our scriptures support this idea of God. And, as a result, I think the slavery example illustrates an exception to SilverRain’s broadly stated position. And, resultantly, we can know that slavery is always wrong, even if an ancient prophet, like Moses, enshrined it in the law.

Of course, Moses could have still been inspired on what to say about slavery. God may have chosen to permit slavery while making sure the Israelites have laws that make slavery less reprehensible than they would have otherwise made it. Taking this position allows slavery to be morally wrong, but doesn’t make God morally culpable, which would be an absurd position to take. Does that make more sense?

Comment by DavidF — November 6, 2013 @ 11:13 am

Sorry about the delay.

“If I understand you correctly, you are saying that we shouldn’t assume that a prophet’s statement accurately depicts an unchanging truth, but we should trust that all prophets’ statements are going to lead us to the grand eternal truths. Is that fair?”

Again, you’re close, but I think we still aren’t quite connecting. My position is that the scriptures cannot be read through lenses which presuppose any kind of fact/value distinction. This, in turn, entails that the absolute foreknowledge of God is NOT anything like that of a Laplacian Demon. In other words, a perfectly complete compilation of non-value-laden facts is not what God’s foreknowledge consists of. Thus, the idea that one prophet’s factual depiction of reality is not logically consistence with another’s factual depiction of reality is not sufficient to show that these prophets are not compatible with each other from a religious perspective. Similarly, the question of whether the later prophet merely unpacks or clarifies the past prophet is totally beside the point as well.

I also think we are talking past each other regarding the difference between an official statement and a prophetic statement. Within our present day context, the only context that really matters, I would suggest that there is no normative difference. In my mind priesthood authority and revelation are two sides of the same coin and cannot be distentangled. If something is canonized or published through official church channels – and it’s pretty obvious when this is the case – it’s prophetic.

I hope from this it is clear why I disagree with your test case regarding slavery. Yes, God encouraged slavery in the OT and prohibits it now. There was no prophet mistake in either case. (Strangely enough, Karl Marx would agree with this.)

Comment by Jeff G — November 6, 2013 @ 8:57 pm

Huh? You’ve completely lost me. I’m not sure what you mean by a fact/value distinction, or non-value-laden facts. But in any conceivable definition that I can think of, slavery seems to be drenched in “value”, so I can’t even begin to see how you decide that God can encourage it and discourage it while being morally consistent.

Let me turn to something I think I can comment intelligently on.

I’m not sure it’s as clear as all that. Which of the following are prophetic, and which aren’t:

-Thomas S. Monson speaks in General Conference

-Monson writes an Ensign article

-Monson speaks at Stake Conference

-At a BYU devotional

-Does your answers to any of the above change if we’re talking about an apostle? A Seventy?

-Samantha Active-Member writes an Ensign article

-First Presidency Statement

-Newsroom statement (no author)

I’m interested in how you parse these hypotheticals out. Why? Because I’m reasonably confident that no prophet has ever told us under what circumstances we can be certain that a prophet’s statement is prophetic. I’ve heard plenty of members say, “Anything spoken in General Conference is binding authority,” but I’ve never heard a prophet claim as much.

Of course, figuring out when a statement is official based on authority and venue gets really tricky sometimes. For example, Brigham Young, as a prophet, preached his rather quirky Adam-God beliefs in multiple conferences (equivalent to a General Conference). Bruce R. McConkie, as an apostle, insisted that Adam-God beliefs are false in a devotional talk (i.e. not in conference). Whose authority takes precedence? Is it obvious? Why is it obvious?

The only thing I can say with certainty about your comment/position is that Marx wouldn’t agree with it. Sure, he thought slavery was a necessary step towards the proletariat revolution, but the similarities end there. And he was wrong.

Comment by DavidF — November 7, 2013 @ 4:18 pm

Well, obviously I’m not doing a very good job, since you are clearly a well-intentioned and well-informed person. I feel like I’ve already address each of those points, but that only means that at least one of us isn’t understanding the other.

Let me try again using the example of Adam-God:

I’ll start with the rejection of any fact/value distinction. This is the ultimate point of my map/compass metaphors from some previous posts. A modern mindset would suggest that God gives us an objective and unchanging map which is destination-neutral. Thus, when BY speaks for A/G and BRM speaks against it, it seems like at least one of these two priesthood leaders is using a bad (false) map.

A pre-modern mind (the mindset by which most of the scriptures were written) seeing God as giving us a compass which points to an objective and unchanging destination. Thus, when BY speaks for A/G and BRM speaks against it, this in no way implies that they are not true in the sense that they both point us to the same objective and unchanging destination. Thus, two statements which cannot both be true from a modern perspective can, from a pre-modern/scriptural perspective both be true.

Let me move on to the question of perumbral cases of officiality. My point was that some doctrines are clearly official and some are clearly not official and some are sort of in between where the question is kind of open. Furthermore, once we combine this point with the above rejection of the fact/value distinction, then some doctrines can drift between all three categories over spatio-temporal contexts. Thus, A/G was probably never totally official (although it might have been). It certainly isn’t now. So what?

Finally, I think this is very similar to Marx’s view concerning slavery and capitalism in that each was/is justified within some context but not others. Furthermore, I submit that Marx’s rejection of the fact/value distinction led him to this conclusion.

Comment by Jeff G — November 7, 2013 @ 5:02 pm

What you are trying to say seems clear to me, Jeff. I think the problem is that this knobs of mystical/intuitive ways of thinking/problem solving is so utterly foreign to our post-Greek, scientific training, you might as well try teach a bird how to breathe with gills.

After watching you try to explain, I’m only left wondering how I managed to naturally think that way, born into this society and culture. Perhaps feeling like a fish out of water isn’t as delusional as I tell myself it is. ;)

Comment by SilverRain — November 7, 2013 @ 6:47 pm

*knobs = kind

Comment by SilverRain — November 7, 2013 @ 6:49 pm

I do think that this version of prophecy and truth are very much alive and well among us. They just tend to get side-lined once educated people start arguing. We talk about true churches, true prophets, etc. These are all pre-modern versions of truth. In the end, I think both versions are always at play in our daily lives, constraining each other.

Comment by Jeff G — November 8, 2013 @ 1:53 pm

Thanks for the clarification. I think your position has a lot of merit, but I’m not convinced that it is absolutely true in all instances.

From your perspective (correct me if I’m wrong), slavery is neither inherently good nor bad, but is only good or bad depending on what God commands.

I’m not sure that our scriptures support this idea. At least, not how I read them. We know that God has at least a fixed moral code on some issues. For example, for whatever reason, God cannot replace justice with mercy. Thus, some acts are inherently morally wrong, with respect to God. And if something is wrong with respect to God, I doubt it can be moral with respect to us.

Is slavery something that is morally wrong with respect to God? That’s probably debatable. Regardless, at least some commandments/revelations are fixed to unchangeable moral principles, and if a prophet were to advocate a position that contradicted an unchangeable moral principle, then that would not only be (theoretically) demonstrable, but also evidence of a prophet making a mistake.

And just to make it clear where I’m going with this: once we allow that a prophet can make a mistake, and his mistake can be evaluated in some way, then we have at least some evidence that in some circumstances a prophet can be demonstrably mistaken on given topic.

Comment by DavidF — November 9, 2013 @ 12:36 pm

The point for me is of course they can make a mistake, but it doesn’t matter. It’s covered.

Comment by SilverRain — November 9, 2013 @ 2:34 pm

Yeah, I still think we are misunderstanding each other in some fundamental ways.

From my perspective, the question of what something is like “inherently” independent of how we interact with it is a meaningless one. The only thing that we can really worry about it how we should engage slavery within whatever context we find ourselves, and there is no reason to think that this should remain constant across all contexts.

“That which is wrong under one circumstance, may be, and often is, right under another. God said, “Thou shalt not kill;” at another time He said “Thou shalt utterly destroy.” This is the principle on which the government of heaven is conducted—by revelation adapted to the circumstances in which the children of the kingdom are placed. Whatever God requires is right, no matter what it is, although we may not see the reason thereof till long after the events transpire.”

Also, I’m not necessarily embracing any sort of divine command theory, wherein something is wrong simply because God says so, although I think this has more truth than falsity to it.

“if a prophet were to advocate a position that contradicted an unchangeable moral principle, then that would not only be (theoretically) demonstrable, but also evidence of a prophet making a mistake.”

There is an awful lot that I disagree with here. First of all, the idea of unchanging moral principles is a mental tool which I see no good use for. It’s not that I agree or disagree with the assertion that they exist, but that I don’t see any good reason for raising that question in the first place.

I also disagree that these things are theoretically demonstrable, as if we were uncovering some objective set of facts regarding universal moral rules which exist independently of all people. The rules which constitute theoretical demonstration are themselves moral rules, and I see no reason why they should nullify any other moral rules when the two sets of rules are brought against each other.

I also don’t see what the fallibility of prophets has to do with anything. Of course, they make mistakes. What does this have to do with the different traditions within which beliefs, words and deeds might be legitimized? In other words, one tradition (intellectualism) takes the beliefs, words and deeds of everybody to ideally be of equal legitimizing value while another tradition (religion) takes the beliefs, words and deeds of a select few of carry greater legitimizing value than those of everybody else. What does the fallibility of anybody have to do with this distinction?

Comment by Jeff G — November 9, 2013 @ 3:37 pm

I’m struggling to see how your position isn’t just a fancy divine command theory.

Taking your position as I understand it: If a prophet makes a prophetic statement, what he says goes, even if it contradicts basic moral beliefs. I have no way of legitimately contradicting him. Even if you aren’t actually advocating a divine command theory, your position seems to functionally operate like a divine command theory with respect to me.

The reason I bring up prophetic fallibility is that if the prophet says something that looks, feels, and seems prophetic, but isn’t actually prophetic, I’m still bound to follow his error, because I have nothing with which to evaluate his prophetic claim. This is because you’ve precluded evaluating a prophet’s claim with appeals to scripture, reason, or any other tool of measurement. I have a tough time buying that God expects me to follow a command that doesn’t actually come from God solely because it appears that it comes from God.

But even backing away from the prophetic fallibility issue, I’m still not sure what ultimately separates your position from a divine command theory.

Comment by DavidF — November 11, 2013 @ 11:07 am

DavidF,

I’ve been thinking quite a bit since you posted the divine command theory post. I still don’t think theyre exactly the same, but the similarities are sufficiently striking that I will certainly have to address this issue in a future post.

There are at least two main differences:

1) The rightness of an action derives not from the divinity of the commander, but the priesthood authority of the commander. In other words, its more like an authoritative command theory.

2) Accordingly, the rightness of an act is not localized to the beliefs, words and acts of a single individual (God).

The similarities with divine command theory include:

A) Authoritative pronouncements are not merely instrumental in nature. The unique authorization of some persons to evaluate certain things, intrinsically justifies their evaluation.

B) The evaluation of some people carries more legitimacy than others solely because of their authority.

Now, of course this authoritative command theory is by no means meant to be the entire picture, but these details which I have pointed out certainly stand in contrast to the moral picture painted by the intellectual.

Comment by Jeff G — November 12, 2013 @ 2:59 pm

Well, I’m interested in seeing you develop this. My gut reaction is to say that the two differences you give aren’t really material. They may make your position unique, but I don’t know if they substantially change the basic ideas of a divine command theory. But maybe when you expand on it, the differences will become a little more obvious.

Comment by DavidF — November 12, 2013 @ 5:41 pm

I too am interested to see how this plays out. You have led me to reconstrue Plato’s Euthyphro dilemma as a strategy whereby he undermined all tradition/authority around him in order to make room for the intellectualism which defined him. Accordingly, if you define “divine command theory” and anything which falls on one side of the Euthyphro dilemma, then I would certainly qualify.

Comment by Jeff G — November 12, 2013 @ 6:37 pm